The Varsity Line closed in 1967. But a head of steam is now building up among politicians and campaigners to reunite Oxford and Cambridge with a direct rail link.

The Oxford-Cambridge arc has been a magnet for high-tech industry, and all the towns along the route are expanding.

Next stop: Cambridge. So read the placards and banners when a group of transport campaigners gathered in Priory Country Park, Bedford, on a Saturday in June. Their plan was to walk the seven-and-a-half miles to the Market Square in Sandy, Bedfordshire, along a footpath and cycleway now given the drab identifier of Sustrans National Route 51.

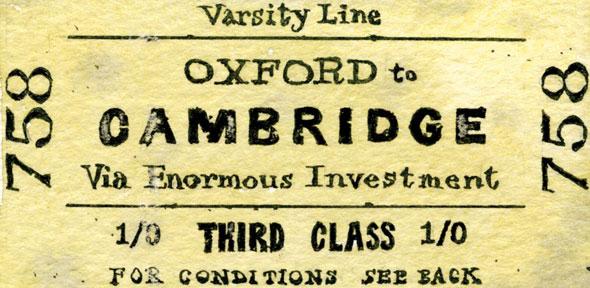

The route’s alternative name – The University Way – offers a clue as to its former use. This was once the trackbed for part of the Oxford to Cambridge railway, popularly known as the Varsity Line or “Brain Line”, until its closure in the late 1960s.

The purpose of the walk was twofold: to celebrate the success of the campaign in restoring rail services between Oxford and Bedford, and to press the case for extending the line all the way to Cambridge. And now, more than ever, there is a sense that trains may once more run between the two university cities without a lengthy detour via London.

Many of those present represented pressure groups and charities that had long been fighting to have the line reopened, including Railfuture and the Campaign for Better Transport. Some were directly involved with the East West Rail Consortium, a group of local authorities and businesses that has taken the helm in developing the case. And reflecting the wide support that the plans have attracted, the walkers included two MPs – Iain Stewart (Milton Keynes South) and Richard Fuller (Bedford) – plus county and district councillors from Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire and Suffolk.

Among them was Noel Kavanagh, a retired business development manager at Cambridge University Press and the transport spokesman for the Labour Party on Cambridgeshire County Council. “I met some of the experts and enthusiasts, which was very enlightening,” he says. “You can certainly learn a lot about rail networks on a walk.”

“I feel optimistic that the plan will come to fruition, as there seems to be a new atmosphere of positivity around it. But these things can take time; and by time, I mean up to a quarter of a century.”

Decline in passenger numbers

In fact, if all goes to schedule and the Oxford to Bedford section opens in 2017, it will be almost half a century after services were withdrawn, and more than 150 years after its original opening. Built in stages between 1846 and 1862, the Varsity Line served stations including Bicester, Bletchley, Bedford and Sandy on its route between Oxford to Cambridge.

Contrary to more than one recent newspaper report, it was not slated for closure in Dr Beeching’s report of 1963. But after a decline in passenger numbers in the subsequent years – in part thanks to faster express trains on an alternate route via London – the last direct service between the two university towns ran in 1967.

Plans to reopen the line have been mooted since the early Eighties, and there have been many false dawns. In 2001, the transport correspondent of the Daily Telegraph confidently reported that “a direct rail link between Oxford and Cambridge is to be restored after 34 years, in a £200million scheme” and that “the aim is to complete the line by 2006”. In reality, the campaign has involved a lot of onerous and unglamorous work – putting together feasibility studies and lobbying local and central government – and the recent success has been hard won.

Peter Wakefield, chairman of the East Anglia branch of Railfuture and a Cambridge resident, says: “It’s a very interesting project in the way it has progressed. In 1995 we put out a pamphlet about the East West Rail plan and sent it to every councillor in Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, and all across to Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Wiltshire. We got an enormous response, and the East West Rail Consortium was formed in 1995.

“Over the years these councils have just beavered away. It really has been a grassroots thing: it hasn’t been from the government down; it has been from the counties and districts up, and these people have really kept at it for the past 20 years.”

Strengthened case

Recently, a number of factors have strengthened the Consortium’s case. The Oxford-Cambridge Arc has become a magnet for high-tech industry, and all the towns along the route are expanding – most notably Bicester and Milton Keynes, with the latter’s population expected to exceed that of Edinburgh within five years. All the while, the region’s transport links have been proving ever more inadequate, with the A14 becoming one of the UK’s most notorious routes for traffic congestion. And on top of this, a new rail route could relieve the overcrowding on commuter rail to the north of the capital.

“The Department of Transport was dismissive at first, but then it started to take it on board,” says Wakefield. “The national railway has become busier and we need new routes for freight and passengers. It has been realised that the route orbiting around the north side of London has huge potential.”

The East West Rail proposals – which in their totality, encompass a connection all the way from Reading to Ipswich and Norwich via Cambridge – now enjoy unprecedented political support. In late 2011, a Parliamentary All-Party Group for the scheme was formed, with Cambridge MP Julian Huppert as vice-chair; and it has been successful in keeping the scheme in the spotlight at a national level.

In January 2013, Network Rail finally announced that the western section of the East West Rail Link would be built as part of its Strategic Business Plan for 2014-19, with the financial backing of the Department for Transport. The target date for services to be operational is December 2017, and there are plans to electrify the line by 2019.

Patrick O’Sullivan, rail consultant for the East West Rail Consortium, says: “We’ve obviously achieved a considerable amount of success on the western section. And that’s because a few things were to our advantage. For one thing, the track is still there – the land has not been sold off and it’s still under the ownership of Network Rail, so there’s no dispute about the route. We’ve been able to prove a very good business case, and it’s been hugely supported by all the local authorities in the area.

“With the success of the western section, we’re now turning our attention to the central section – not that we ever forgot about the central section, because an awful lot of work has been done on it.”

Range of alignments

Building the central section is a far trickier proposition. Aside from the stretch between Bedford and Sandy that has been retained as a footpath, following the old route is no longer possible. O’Sullivan says: “The problem with Bedford to Cambridge is that the railway has been dismantled, land has been sold off and developed over – not least by Cambridge University, whose radio telescopes sit on the line. Which is not helpful!”

To date, there is no agreement as to the route that a Bedford-Cambridge link could take. And this is where the consensus that has been painstakingly built over the past 20 years could begin to crumble. Authorities in the north of the region are likely to favour a reasonably direct route between the two places. Those living in Hertfordshire and Luton, however, may well prefer to take the line via Luton and Stevenage; and there are a range of other alignments that are under consideration, each with potential to link up other communities in the region.

The Consortium is now taking a step back, having appointed consultants to come up with a definitive study into the economic case for each route option. “Rather than just looking at how to get from A to B, we’ll be doing a study of the whole region, looking at what’s driving the economy, what’s the potential for development and how transport links can help that development,” says O’Sullivan.

He is adamant that this is a time for being hard-headed, and putting aside romantic notions of restoring the once-loved Varsity Line. “This can be the danger of rail enthusiasts,” he says. “They want to reopen the railway because it used to be there. It’s a bit like bringing back steam trains, though that’s exaggerating the point to make the point.

“It’s going to cost not far short of a billion pounds to build a new railway between Bedford and Cambridge, and you’ve got to ask what the benefits are of spending a billion pounds of probably public money.”

Nevertheless, O’Sullivan thinks that there is a great likelihood of a full Oxford-Cambridge service getting the green light in the medium term. The Department of Transport works to five-year cycles, and he believes a realistic aim is for confirmation in the 2019-2024 “control period”.

“There’s an awful lot of political support for reopening a route to Cambridge,” he says. “Ironically, the politicians at Westminster are more supportive of the central section than they were of the western section – although they obviously welcomed that reopening.

“But because it’s going to be so expensive, the benefits will need to be very, very high to mitigate the capital cost of the scheme. So that’s where we are at the moment. There’s lots of support for doing it; but we’ve got to do a lot of work to make a case for it.”